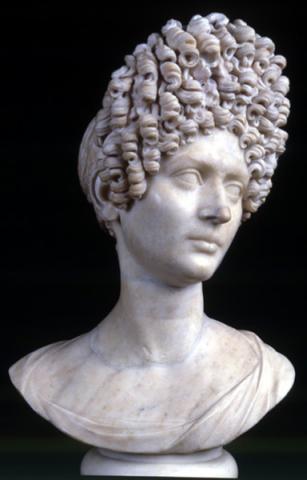

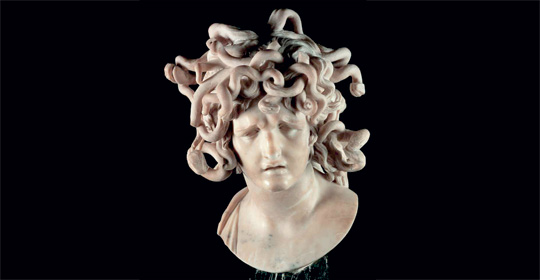

Restoration of the Bust of Medusa by Gian Lorenzo Bernini

As part of the project “FIT for Art and Culture”, the Federazione Italiana Tabaccai & Logista Italia have financed the restoration of the Bust of Medusa by Gian Lorenzo Bernini and its 18thcentury base.

The sculpture, a gift from the Marquis Francesco Bichi, Conservator of the first quarter of the year 1731, is documented for the first time in the Inventories of the Palazzo dei Conservatori of 1734 in the Sala delle Oche, an original location where it has remained until today.

The conservative restoration, directed by Elena Bianca Di Gioia, was designed and carried out by the restorers Tuccio Sante Guido and Giuseppe Mantella.

The multispectral investigations were accomplished by Maurizio Fabretti, the spectrophotometric ones by Costanza Miliani; the sculptural technique was investigated by Peter Rockwell; the graphic elaborations were carried out by Monica Cola, while the photographic documentation was realised by Andrea Jemolo.

The intervention involved the following phases:

- Non-destructive cognitive investigations: multispectral investigations (infrared and ultraviolet), spectrophotometric investigations, documentation and graphic rendering with optical instrumentation; photographic documentation.

- Study of sculpture execution techniques with identification of the marks left by the different tools used. Study and identification of the surface finishing technique considering the most updated methodologies applied to the restoration of Gian Lorenzo Bernini's sculptures.

- Surface restoration, preceded by gradual cleaning assays supported by the localized application of multispectral investigations.

The main novelties that emerged concern the accurate detection of the state of conservation of the sculpture and its processing technique.

The data collected offered food for thought in an attempt to clarify some aspects of the genesis and conservative history of the work.

The non-destructive multispectral investigations, aimed at detecting the different layers of patina present on the surface of the sculpture, were necessary to grade the cleaning intervention and minimize the risks of removing the original finish.

The four-month works were designed as an open site. Visitors were able to observe directly the various phases of the restoration.

For more information, go to www.tabaccai.it and www.logista.it

Bust of Medusa - Gian Lorenzo Bernini (Naples 1598-Rome 1680)

the fourth - fifth decade of the seventeenth century

Carrara marble

Dimensions: approx. 50 x 41 x 38 cm

portoro spool piece: h. 18 cm, diam. 20 cm.

18th century base in coloured marble veneer; from the bottom upwards: antique grey, African marble, hymettian, antique yellow, antique green, Caria red, alpine green;

on the left side engraved on the marble: coat of arms of the Senate and Roman people

on the right side: Bichi emblem

on the front side inscription engraved in capital letters:

"MEDUSAE IMAGO IN CLYPEIS / ROMANORUM AD HOSTIUM / TERROREM OLIM INCISA / NUNC CELEBERRIMI / STATUARIJ GLORIA SPLENDET / IN CAPITOLIO / MUNUS MARCH: / FRANCISCI BICHI CONS: / MENSE MARTIJ / ANNO D. / MDCCXXXI."

"The head of Medusa, in ancient times used as ornamentation on the shields of the Romans to terrorize their enemies, today shines brightly in the Capitol, glory of the renowned sculptor, a gift of the Marquis Francesco Bichi, Conservator in March of the year of the Lord 1731".

Provenance: gift from the Marquis Francesco Bichi, Conservator of the first quarter of the year 1731. The Bust of Medusa and the base have been documented since 1734 in the Sala delle Oche; inventory S / 1166.

In the Metamorphoses, Ovid narrates that Medusa, the most beautiful and deadly of the Gorgons, had the power to petrify anyone who dared gaze into her eyes.

Surprising her while sleeping, Perseus managed to cut off her head by looking at the image reflected in the bronze shield donated to him by Minerva.

After freeing Andromeda and defeating Phineus thanks to the intact petrifying power of Medusa's head, the hero gave it to Minerva who placed it as an ornament of his aegis and then of his shield, as a terrible weapon to defeat the enemies of the reason and wisdom, virtues she embodied.

Hence the very ancient custom, used in the Renaissance, to adorn battle and parade shields with the Medusa's Head as a weapon to terrorize enemies, but also a symbol of the virtue and wisdom of whoever held the shield.

Bernini disregarded the depiction of the truncated head of Medusa proposed by classical, Renaissance and Mannerism sculpture, skilfully revived in the last decade of the 16th century in Rome by Caravaggio, in the parade shield painted for Cardinal Del Monte, later donated to the Grand Duke Fernando de’Medici and by Annibale Carracci in the frescoes painted between 1598 and 1601 in the Galleria of Palazzo Farnese. He sculpted a true bust - portrait of Medusa, alive, caught in a transitory moment of unique “metamorphosis”.

The myth narrated by Ovid, wherein the beautiful blonde hair of Medusa is transformed into horrible serpents by Minerva as a punishment for having had intercourse with Neptune in the Temple of the female divinities of Faith and Truth, is revisited in a completely original manner in some poetic verses by Giovan Battista Marino.

In a well-known madrigal taken from La Galeria (1620, I, 272), the poet pretends that it is a wonderful statue of Medusa that is speaking: "(…) Non so se mi scolpì scarpel mortale, / o specchiando me stessa in chiaro vetro / la propria vista mia mi fece tale".

(“I don’t know if a mortal chisel sculpted me /or whether by looking at myself in clear glass/ the very sight of myself made me so.”)

The classical myth is overturned to exalt the virtue of the unknown sculptor: it isn't the Gorgon who petrifies her enemies with her gaze, but it is Medusa herself who, looking at her image in a mirror by fatal error, seems to have turned into marble.

Considered by the critics as one of the most problematic works of Gian Lorenzo Bernini, it was probably created in the first years of Innocent X Pamphilj's pontificate, between 1644 and 1648, when the artist was removed from the papal court because he was a favourite of the Barberini and at a time when his fame had been temporarily diminished on account of the professional humiliation caused by the demolition of the bell tower of St Peter's Basilica (1646).

The Bust of Medusa seems to be one of those sculptures carried out “for his study and pleasure” (as was the case of the Truth in 1646 which remained in his studio and was tied to his family by will), the result of a personal meditation by the artist on the aims of sculpture and the virtues of the sculptor (Lavin, 1996).

In this work, which has no iconographic or iconological precedents in his extremely original interpretation of the myth, the sculptor takes up anew the comparison between sculpture and poetry already developed in the youth groups for cardinal Scipione Borghese. But after Virgil and Ovid, it is Marino's poetry that gives him the idea to “autenticar coi fatti il suo valore" (“authenticate his value with facts”) and defeat his enemies and detractors in one of the most critical moments of his career.

Medusa, with a classically beautiful face and delicate features, sees herself in an imaginary mirror and is caught in the moment when she realises the atrocious trick of fate, and before our very eyes, her soft flesh fades away, the writhing snakes in her hair freeze and her expression of pain and anguish are forever captured in marble.

It is another proof of Bernini's ability to capture the climax of a transitory action and the contradictory complexity of human emotions in his sculpture.

Although, the Bust of Medusa was also intended by the artist to be a refined Baroque metaphor on the power of sculpture and the value of the sculptor.

As Medusa “dimostra la vittoria, che ha la ragione degli inimici contrarij alle virtù” (“demonstrates the victory of reason over the enemies of virtue”) (Cesare Ripa, Iconologia, 1603,426), Bernini's Medusa leaves his enemies and detractors literally “petrified” in astonishment by using his sharpest weapon: the virtue of his chisel.

In an essay reworked by Irving Lavin for the volume dedicated to the restoration just concluded, the scholar returns to the subject with new reflections and establishes a closer relationship between the Bust of Costanza Bonarelli, sculpted between 1636 and 1638, and that of Medusa, perhaps made by Bernini as a moral contrast to the first, both however conceived as a very personal reflection of the artist and both subsequently donated or transferred to others by the author.

Based on this new hypothesis of reading the work, the dating of the Bust of Medusa could be slightly anticipated in the late thirties of the seventeenth century.

The book edited by E. B. Di Gioia, "Il Busto di Medusa di Gian Lorenzo Bernini. Studi e restauri" was published by Campisano Editore at the conclusion of the restoration.