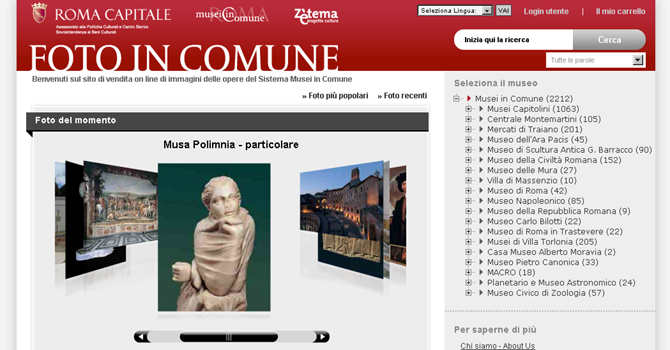

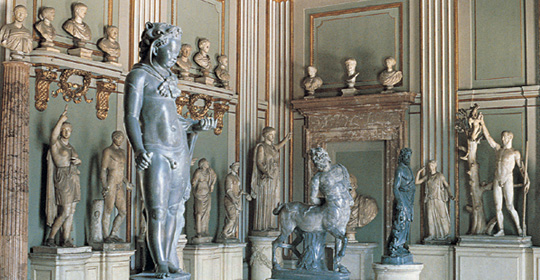

Restoration of the sculptures in the Hall of Palazzo Nuovo

Gioco del Lotto-Lottomatica is financing the restoration of an important sculptural group on display in the Hall of Palazzo Nuovo, one of the groups that best represents the entire Capitoline collection.

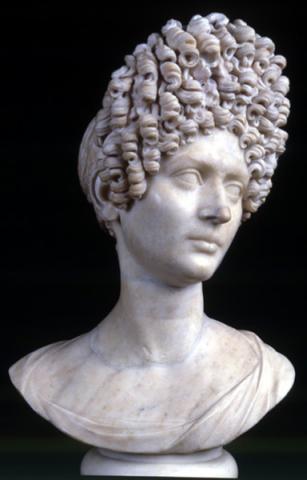

The objects to be worked on are sixteen pieces of marble sculpture in the round, all of which life-size or over, and two figured cylindrical altars also in marble.

It is a restoration work of considerable commitment and interest, which access the full potential of an ancient sculpture of great importance, removing the thick layer of dirt accumulated over the centuries; in particular, it will be possible to recognise the ancient parts from the modern reconstructions made in the seventeenth century to fill in where parts were missing.

The works, of an expected duration of eighteen months, have the form of an open site, allowing visitors to directly observe the progress of the restorations at each stage in the museum itself.

The sculptures were purchased in 1733 by Pope Clement XII Corsini with the proceeds of the Lotto Game, institutionalised by the Pope himself, lifting the prohibition with excommunication issued by his predecessor Benedict XIII and arranging that the revenues were used for charitable and public utility works.

For a first period, the draws took place on the Piazza del Campidoglio, with great popular participation.

In 1733, in addition to the purchase for the considerable sum of 66,000 gold ecus from the most important private collection of antiquities present in Rome, which belonged to Cardinal Alessandro Albani, with the proceeds of the lot, financed also the readjustment works as a museum space of the Palazzo Nuovo, at the foot of the church of S. Maria in Ara Coeli.

The sculptures subject to the restoration

-Statue of Apollo Citaredo (inv. MC 0628)

-Statue of Athena (inv. MC 0629)

-Bust of Trajan (inv. MC 0630)

-Statue of Augustus (inv. MC 0631)

-Statue of Hera (inv. MC 0632)

-Statue of an athlete (inv. MC 0633)

-Statue of the so-called Mario (inv. MC 0635)

-Statue of a Roman as a hunter (inv. MC 0645)

-Statue of a Roman lady, depicted as Hygieia (inv. MC 0647)

-Statue of Apollo (inv. MC 0648)

-Statue of Pothos (inv. MC 0649)

-A couple of Romans depicted as Mars and Venus (inv. MC 0652)

-Statue of Muse (inv. MC 0653)

-Statue of Athena (inv. MC 0654)

-Statue of Zeus (inv. MC 0655)

-Statue of Asclepius (inv. MC 0659)

-Circular base with divinity (inv. MC 1995)

-Circular base with the scene of sacrifice (inv. MC 1996)

The Capitol and the Lotto game in Rome in the eighteenth century

In past centuries, the game of lotto in the State of the Church enjoyed mixed fortunes. Throughout the sixteenth and part of the seventeenth century the lottery, like all games related to fate, was considered to be decidedly contrary to the principles of Catholic morality since it pushed human beings to rely on chance rather than their own personal skills to improve their existence, not following the designs of Divine Providence. The judgment in some periods was so negative that the popes felt the obligation not only to ban the game of the lot in any form but also to order punishments of the utmost severity for offenders, who came under Benedict XIII (1725) to excommunication.

Nonetheless, the game continued to have great popularity among all social classes that Pope Clement XII Corsini, who rose to the papal throne in 1730, saw the need to re-examine the whole matter with a pragmatic spirit, with a particularly attentive eye to financial aspects (he had been Cardinal Treasurer of the Apostolic Chamber, the equivalent of our Minister of Finance).

The pope estimated that the prohibition of the lottery game had led to considerable popular discontent and an uncontrollable outflow of capital to those countries where gambling was allowed; he also considered that the public establishment of the lot would have made it possible to dispose of significant quantities of money, without resorting to additional or more expensive forms of taxation than the existing ones. To make it acceptable, even for contemporary Catholic morality, he ordered that the proceeds from the lottery game be used exclusively for charitable works (support for apostolic missions; construction, restoration and management of hospitals and places of worship; almsgiving to the needy; etc ... ) and of public utility.

Thus, on December 9, 1731, as part of the interventions in support of public finance, the game of lotto was definitively institutionalized, and the prohibition with excommunication issued by the predecessor Pope Benedict XIII was revoked.

Great was the success, as found in the chronicles of the time, of the first draw which took place on February 14, 1732 on the Piazza del Campidoglio. So large was the influx of people that the square was unable to contain all the bystanders, who gathered along the access cordon and occupied the access roads to the hill on the slopes.

The success of the game was immediate and lasting, allowing the pontifical coffers to dispose of significant quantities of money to be used for institutional purposes.

This sudden financial availability allowed Pope Clement XII, well advised by his nephew, Cardinal Neri Corsini, to promote the building renovation of Rome in a few years with the construction, among other things, of the facade of S. Giovanni in Laterano, the Palazzo della Consulta at the Quirinale, the Trevi Fountain, the facade of S. Giovanni dei Fiorentini.

The fact that the draw of the lot took place on the Piazza del Campidoglio, with such great popular participation, prompted Pope Clement XII to turn his attention also to the Capitoline hill and its monumental buildings. In particular, since 1733, it was ordered that the Palazzo Nuovo, rising at the foot of the church of S. Maria in Ara Coeli, freed from previous administrative functions, would be used as a Capitoline Museum. For this purpose, the most important private collection of antiquities in Rome, which belonged to Cardinal Alessandro Albani, was purchased for the considerable sum of 66,000 gold ecus.

It is a measure of significant symbolic and cultural value aimed, on the one hand, at awarding the state and the public enjoyment of an invaluable heritage at risk of dispersion, on the other at promoting the image of Rome and contributing to the growth of sensitivity artistic and historical for the new generations.

The purchase of the Albani collection and the adaptation works of the Palazzo Nuovo to the museum functions entailed a considerable financial effort, fully supported by the proceeds from the game of the lot, used since then continuously for the acquisition, protection, conservation and use of the historical-artistic and more particularly archaeological heritage (the restoration of the Arch of Constantine, for example).

The importance of the proceeds from the lotto game for interventions of cultural value will not fail in the following decades, but rather will be consolidated with the new extraordinary museum enterprise promoted by the popes in Rome: the institution of the Vatican Museums in 1771.

It should be remembered, finally, as the example offered by Rome, it was soon adopted even beyond national borders. In Britain, in fact, in the nineteenth century, the proceeds from the lotteries served to create the British Museum; while in the United States they were intended for the establishment of the universities of Yale, Harvard and Princeton.